This Shabbat marks the absolute completion of the intense cycle of holidays

that began with Rosh Hashanah, almost one month ago. We have welcomed a

new year, 5773; we have repented for our transgressions and sought forgiveness from

God and from others around us; we have celebrated the unadulterated joy of

Sukkot and all of the ritual symbols that go with it; we have mourned those who

have passed from this world on Shemini Atzeret, we have danced with the Torah

in soaring jubilation as we finished reading one

complete cycle of the Pentateuch, the Five Books of Moses.

And on this Shabbat we begin that cycle again with the reading of the first of fifty-four parashiyyot / weekly portions into which the Torah is divided. This is Shabbat Bereshit, the Shabbat of Creation, and today’s parashah is filled to overflowing with precious gems. On this Shabbat we commemorate not only the creation of the world, but also the creation of the principle of Shabbat itself, arguably the most important feature of human existence that the Jews gave to the world: the weekly vacation day that allows all of us to recharge.

But what I think is most wonderful about Parashat Bereshit is not the two tales of Creation: the orderly seven-day epic of God’s fashioning each piece of the universe or the Garden of Eden story. It is not the Torah’s attempt to answer the most primal philosophical Big Questions -- where we came from and how. It is not the beginning of humankind or even the question of Homo sapiens sapiens’ apparent dominion over all of the Earth (Gen. 1:28) vs. our obligation “to till and to tend” the Earth (Genesis 2:15).

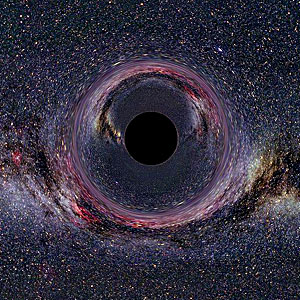

No. What is truly the most wonderful feature of this parashah is the preponderance of holes found within it. The Torah’s opening stories are far from airtight; they are riddled with openings.

(When I was an undergraduate, I fulfilled my required semesters of phys. ed. by learning Tae Kwon Do. This Korean martial art involves many kicks, and requires much flexibility in the legs, and we performed a lot of painful stretches. I’m just not that flexible. So one day, I’m trying valiantly to keep my left leg straight against the gym floor while stretching out over my right leg, when the Korean taskmaster -- I mean, teacher -- swipes his hand underneath my left leg, where there are several inches of clearance, and says, “Look at this! You could drive a truck through there!” Those are the kinds of holes we have in Bereshit.)

And on this Shabbat we begin that cycle again with the reading of the first of fifty-four parashiyyot / weekly portions into which the Torah is divided. This is Shabbat Bereshit, the Shabbat of Creation, and today’s parashah is filled to overflowing with precious gems. On this Shabbat we commemorate not only the creation of the world, but also the creation of the principle of Shabbat itself, arguably the most important feature of human existence that the Jews gave to the world: the weekly vacation day that allows all of us to recharge.

But what I think is most wonderful about Parashat Bereshit is not the two tales of Creation: the orderly seven-day epic of God’s fashioning each piece of the universe or the Garden of Eden story. It is not the Torah’s attempt to answer the most primal philosophical Big Questions -- where we came from and how. It is not the beginning of humankind or even the question of Homo sapiens sapiens’ apparent dominion over all of the Earth (Gen. 1:28) vs. our obligation “to till and to tend” the Earth (Genesis 2:15).

No. What is truly the most wonderful feature of this parashah is the preponderance of holes found within it. The Torah’s opening stories are far from airtight; they are riddled with openings.

(When I was an undergraduate, I fulfilled my required semesters of phys. ed. by learning Tae Kwon Do. This Korean martial art involves many kicks, and requires much flexibility in the legs, and we performed a lot of painful stretches. I’m just not that flexible. So one day, I’m trying valiantly to keep my left leg straight against the gym floor while stretching out over my right leg, when the Korean taskmaster -- I mean, teacher -- swipes his hand underneath my left leg, where there are several inches of clearance, and says, “Look at this! You could drive a truck through there!” Those are the kinds of holes we have in Bereshit.)

But here, in the Torah, that’s a great thing. One could make the

point, by the way, that all of Judaism is fashioned from the openings in the

text of the Torah (I’ll give examples in a moment). The entire enterprise

of rabbinic Judaism, the intellectual give-and-take that emerged in the

centuries following the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70

CE, is based on disagreement over points of ambiguity found in the Torah.

The first verse of the Torah is (Genesis 1:1, Etz Hayim p. 3):

The first verse of the Torah is (Genesis 1:1, Etz Hayim p. 3):

בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת

הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃

Bereshit bara Elohim et hashamayim ve-et ha-aretz.

Rashi, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaqi, the great 11th-century French commentator and democratizer of the Torah, is awestruck at the mystery and power behind these opening words.

Rashi, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaqi, the great 11th-century French commentator and democratizer of the Torah, is awestruck at the mystery and power behind these opening words.

אין המקרא הזה אומר אלא דרשיני

Ein hamiqra hazeh omer ela “Darsheini!”

This text only says, “Explain me!”

It is calling out to us from the pre-Creation tohu vavohu, the concealed, chaotic mists of pre-history, beckoning to us to interpret. So says Rashi.

You see, bereshit bara Elohim makes no sense! It is grammatically incorrect. It does not mean (as we have come to hear it courtesy of King James), “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth.” Rather, it means, “In the beginning of [fill in the] BLANK, God created heaven and earth.” Or maybe it means, “In the beginning of God’s creation of heaven and earth....” Or maybe (as it says in our humash), “When God began to create heaven and earth...” Or something else entirely that we’re simply not expecting.

There is something missing. And that missing word, or phrase, or concept, is where all the action is. That is where we find ourselves reflected in the text. We can drive whole fleets of trucks through that hole. It is a vacancy that will never be filled, an opening that can accommodate any idea that you can fit. The mystery remains permanently enshrined in the first three words of Genesis.

Here is another example. Some time later, after Eve and Adam are exiled from the Garden, their sons Cain and Abel squabble over who is favored by God. As I am sure that you know, Cain kills his brother Abel in cold blood. But just prior to the invention of fratricide, Cain says something to his brother, something which does not appear in the Torah (Gen 4:8, Etz Hayim p. 26):

This text only says, “Explain me!”

It is calling out to us from the pre-Creation tohu vavohu, the concealed, chaotic mists of pre-history, beckoning to us to interpret. So says Rashi.

You see, bereshit bara Elohim makes no sense! It is grammatically incorrect. It does not mean (as we have come to hear it courtesy of King James), “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth.” Rather, it means, “In the beginning of [fill in the] BLANK, God created heaven and earth.” Or maybe it means, “In the beginning of God’s creation of heaven and earth....” Or maybe (as it says in our humash), “When God began to create heaven and earth...” Or something else entirely that we’re simply not expecting.

There is something missing. And that missing word, or phrase, or concept, is where all the action is. That is where we find ourselves reflected in the text. We can drive whole fleets of trucks through that hole. It is a vacancy that will never be filled, an opening that can accommodate any idea that you can fit. The mystery remains permanently enshrined in the first three words of Genesis.

Here is another example. Some time later, after Eve and Adam are exiled from the Garden, their sons Cain and Abel squabble over who is favored by God. As I am sure that you know, Cain kills his brother Abel in cold blood. But just prior to the invention of fratricide, Cain says something to his brother, something which does not appear in the Torah (Gen 4:8, Etz Hayim p. 26):

וַיֹּ֥אמֶר קַ֖יִן אֶל־הֶ֣בֶל אָחִ֑יו

וַֽיְהִי֙ בִּֽהְיוֹתָ֣ם בַּשָּׂדֶ֔ה וַיָּ֥קָם קַ֛יִן אֶל־הֶ֥בֶל אָחִ֖יו

וַיַּֽהַרְגֵֽהוּ׃

Cain said to his brother Abel, "BLANK." And when they were in the field, Cain set

upon his brother Abel and killed him.What could he possibly have said? “Abel, there’s something I’ve been meaning to tell you.” or “You know, I’d be much happier if I were an only child.” Or maybe, “Hey, bro. Your shoe’s untied!“ The 3rd-century BCE Greek translation known as the Septuagint actually has a line here that the Torah does not -- Cain says, “Come, let us go into the field.”

The Septuagint notwithstanding, there are many possibilities here, and not a single one of them is wrong. We can imagine many things that Cain might have said just prior to murdering his brother - venting his spleen, or confessing his jealousy and love and pain, or even asking his brother for forgiveness for what he has long been planning to do.

That’s where you come in. The Torah is not complete without us. While it would not be accurate to say that the Torah is a blank canvas upon which we can paint whatever we want, it is certainly not true that the words of the Torah alone give us a clear, fixed, immutable message. The very essence of Judaism, in fact, throughout history has been the interpretation of the words of Torah by us. By humans. Because what we received from God, the scroll of parchment that we read from every Shabbat and Monday and Thursday, is in many ways just a sketch.

There is a well-known Talmudic story (BT Menahot 29b) about how when Moses went up on Mt. Sinai to receive the Torah, and he finds God putting little crowns on some of the letters. Moses asks God, “Ribbono shel olam, Master of the universe, what are you doing?”

God replies, “More than a thousand years from now, a scholar named Rabbi Akiva is going to infer many things from these crowns.”

Moses asks, “Can I see this guy?”

God says, “Turn around.” So Moses does, and he is instantly transported into the classroom of Rabbi Akiva in Palestine in the early 2nd century, CE. Moses is sitting in the back behind eight rows of students, and he is listening to Rabbi Akiva interpret the very words of Torah that Moses himself had transcribed. But he can’t understand any of what Rabbi Akiva is saying, and he starts to feel queasy.

One of the students asks, “Rabbi, where did you learn all of this?”

Rabbi Akiva says, “It was given to Moses on Mt. Sinai!” And Moses feels much better.

He is relieved because he understands that those parts of the Torah that Moses himself cannot understand will eventually be interpreted by us. The crowns, which are meaningless to Moses, are explained by Rabbi Akiva, and Moses sees then that everything in the written text is subject to later human analysis. Now of course, nobody alive today can interpret the Torah with the authority of Rabbi Akiva. But on some level, each of us is obligated to personalize our relationship with God, the Torah, and Israel, to fill in those holes and seek meaning from not just the letters and words themselves, but crowns and the spaces in-between.

Many of us personalized the sukkot in which we dined and welcomed guests last week. I hope that your Pesah seder includes discussion about how we each identify with the Exodus story and the lessons that we draw today from seeing ourselves as having personally come forth from Egypt. And each of us, when we hear the Torah read in the synagogue or study it in another context, should strive to connect with the words in a way that is meaningful for us.

But this idea goes far beyond the ritual aspects of Judaism. The Torah urges us to take care of the needy in our neighborhood, and it is up to us to figure out how to do so. The Torah requires us to honor our parents, and we each find our way through the depth and complexity of these relationships. The Torah tells us to teach our children about our tradition, and each of us makes judgment calls about what we teach and how we teach and whom we task with assisting us in doing so. The Torah instructs us to treat our customers and vendors fairly, and the burden is on us to make sure that we find the right way to do so.

What is missing from the Torah? You. Each one of us.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Temple Israel of Great Neck, Shabbat morning, October 13, 2012.)

No comments:

Post a Comment