When I was in rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological

Seminary, I took a philosophy course that examined contemporary spirituality.

The professor, a somewhat non-conventional rabbi, Rabbi Alfredo

Borodowski, emphasized that the primary struggle of religion in our day is to

bring meaning to people’s lives. Some of the questions that we ask are:

What does our tradition teach me?

How can I apply it to my life today?

I only have so much time and so much energy, so if I am

going to pay attention to anything, it better be meaningful. What can I

possibly gain from paying attention to Jewish life?

This search for meaning is bound up in our character; it

is the reason that we are called “Yisrael,” the name given to our patriarch Jacob

as “one who struggled with God and with humans” in Genesis 32:29.

Our job as a Jewish community is to answer the question,

“What does this mean to me?” Yes, we must offer many points of entry.

Yes, we must be open, welcoming, and accessible. But even with all

that, we have to offer deep, serious, meaningful content alongside the

opportunity to interact with God.

It’s not enough, for example, for a synagogue to offer services

on a Saturday morning and merely expect that people will show up, no matter how

wonderful the sermon or the cantor’s vocal pyrotechnics. For people to

come, even those who grew up going to shul, there has to be some meaning

to it.

It’s not enough to encourage 7th-grade students to

continue on into the Youth House Hebrew High School program after they have

completed their Bar/Bat Mitzvah. Those kids have to see that there is

some value, some personal meaning in continuing their Jewish education, and

their parents have to see this as well. We have to demonstrate that

value, teach that meaning. If we do not, they are not coming back.

It’s not enough for me to stand here before you and talk about

the essential mitzvot / commandments of Jewish life, like the observance

of Shabbat and kashrut, without making a case for how doing so will mean something

to us as individuals and the community. Otherwise, such suggestions will

not be heard.

***

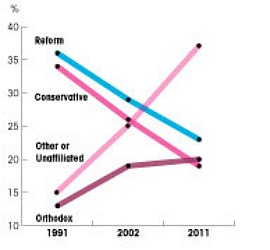

Perhaps some of you saw the results of a demographic studythat came out two weeks ago, funded by the UJA-Federation of New York.

The conclusions were not surprising, although the Jewish newspapers spun

it as big news. Among the major findings were the following: New York

Jewry saw a small uptick in population, and most of the growth was in the

Haredi / “ultra-Orthodox” sector. Jews in the metropolitan area are on

the one hand growing more rigorously traditional and on the other more unaffiliated,

and particularly less identified with the Conservative and Reform movements.

To be fair, this study does not represent the entire

region -- only NYC and Westchester, Nassau and Suffolk counties. As

journalist J. J. Goldberg pointed out in the Forward, the 1.5 million Jews

counted excluded about 500,000 who live in NJ and Connecticut, and those

numbers skew more heavily non-Orthodox.

(By the way, while it is true that Orthodoxy saw growth

since the last study in 2002, it might be worth noting that Haredi families

average something more than six children per family. Conservative families

have an average of 1.5 children. I’ll leave the math to you.)

The biggest point of concern from my perspective,

however, is the dramatic growth of the category known as “Other.” More

than a third, 37% of area Jews, identified themselves as something other than

Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox. Those categories include “just

Jewish,” “something else,” “no religion,” non-Jewish religion (but respondent

is Jewish), “traditional,” “Sephardic,” “cultural,” “secular,” and other

answers.

(from forward.com)

But what do these numbers mean? Aside from the

obvious conclusion that the non-Orthodox movements are shrinking (which, by the

way, has been true for several decades), the more accurate observation is as

follows: We must be doing something wrong. Why are younger people who

grew up in our movement not joining synagogues or signing up their kids for

Hebrew school or even identifying themselves as “Conservative” when a pollster

calls? Maybe it’s because we are expensive, and Chabad is cheap.

Maybe it’s because we stand for Israel in a world that has grown hostile

to the Jewish state. Maybe it’s because assimilation has led our people

astray.

Or maybe it is because we have not made an adequate case

for why the non-Orthodox Jewish experience is meaningful.

You see, Orthodoxy has a strong, built-in meaning machine.

It’s what much of our tradition says over and over: buy into the system,

accept the yoke of halakhah, and it will be good for you. I know people

who have left the non-Orthodox fold for frummer pastures because it all seems

so simple: do what we tell you and it will all make sense. Much of

Orthodoxy includes with that the very simple condition of not asking questions

that probe too deeply, such as, “Why are women excluded from Jewish rituals?”

Or, “Why must there be only one path to God?”

But our message, the Conservative Jewish message,

reflects the richness of humanity and the complexity of the Jewish textual

discourse. Life is not black and white, and neither is rabbinic

literature, or for that matter, the Torah. There is always a dissenting opinion;

there is always room for debate. The Talmud teaches us that women can be

called to the Torah in synagogue and wear tallit and tefillin.

Conceptions of God by modern philosophers such as Abraham Joshua Heschel or

Martin Buber are as relevant as the Torah’s multiple perspectives.

To arrive at the meaning, however, you have to dig deeper,

says the Conservative movement. It is not enough just to recite the words

of tefillah / prayer quickly and accurately, it is just as important to understand

them, and to re-interpret them for our times. There is more meaning in mindfulness

than in performing rituals by rote.

I find meaning, and I hope that some of you do as well,

in careful analysis, in familiarizing ourselves with these ancient texts and

making them come alive. I also find meaning in asking the hard questions:

“How can I believe in a God that allowed the Shoah to happen?”

“How can I accept the stories of the Torah at face value when they

sometimes contradict scientific principles or archaeological evidence?”

Disagreement is an ancient tradition, and should be

encouraged. Tolerating multiple opinions was something that came out of rabbinic

tradition, and is even highlighted as being “leshem shamayim,” as having

a Divine purpose. As we read in Pirqei Avot, the book of the

Mishnah dedicated to 2nd-century rabbinic wisdom on life and learning:

Avot 5:17:

כל מחלוקת

שהיא לשם שמיים, סופה להתקיים; ושאינה לשם שמיים, אין סופה להתקיים. איזו

היא מחלוקת שהיא לשם שמיים, זו מחלוקת הלל ושמאי; ושאינה לשם שמיים, זו מחלוקת

קורח ועדתו.

Every disagreement that is for the sake of heaven will

stand; every one that is not for the sake of heaven will not stand. What

is a disagreement that is for the sake of heaven? One between Hillel and

Shammai. What is a disagreement that is not? The one concerning Korah and

his sympathizers.

The disagreements between Hillel and Shammai, two schools

of thought referenced in the Talmud, are usually about finer points of halakhah

/ Jewish law. (A classic dispute, one that I know that is taught in our

Religious School, is how to light the Hanukkiah, the Hanukkah menorah.

Shammai says to start with 8 candles the first night, and to lose one on

each successive night; Hillel says that we should start with 1 and go to 8, as

we all do today.)

Korah, however, brought

together a group of malcontents merely to struggle against Moses and Aaron,

claiming an unfair distribution of power. In pleading his case before

Moses, he said:

כִּי

כָל-הָעֵדָה כֻּלָּם קְדֹשִׁים, וּבְתוֹכָם ה'

For all of the community

are holy, all of them, and the Lord is in their midst. (Numbers 16:3)

In other words, we are all endowed with some

of God’s holiness, says Korah. What makes you guys, Moses and Aaron, so special?

Rashi concurs, offering that all the Israelites stood at Mt. Sinai together,

not just Moses and Aaron. Korah is advocating for a share in leadership

that he thinks that he deserves.

On some level, Korah is right: we all do have

a share of the Divine. We all stood at Mt. Sinai. We all received

the Torah.

And this is still true, by the way.

Regardless of the validity of Korah’s claim on leadership, and regardless

of what synagogue we choose to attend or join or not, there is no question that

we all have a share in the Torah, a share in holiness.

In today’s complex, multi-layered Jewish

world, we do not necessarily disagree about the meaning of the text. More

pointedly, what we disagree about is the “how.” How do we create holy

moments? How do we relate to Jewish law? How do we observe?

How do we make our tradition relevant?

This is, in fact, the essential mahloqet

leshem shamayim, disagreement for the sake of heaven, of our day. This

disagreement an essential part of who we are. Remember that we are Yisrael,

the ones who struggle with beings Divine and human. We challenge ourselves

as much as we challenge God.

But we cannot let this dispute distract us

from our holy task -- that is, bringing meaning to all those who enter this

building. As Rabbi Howard Stecker pointed out to me the other day when we were

discussing this, what were the people doing while the leaders were arguing?

Did Korah’s dispute pull Moses and Aaron from their holy work?

Perhaps that is precisely why the Mishnah labels this as an un-heavenly

debate.

**

The fifth line on the chart, the one that we

do not see, is the line of the “Unaffiliated, but Potentially Engaged.”

Or maybe “Unaffiliated, but Still Seeking.” That line is also on

the way up. It may not include all of the Unaffiliated, but it certainly

includes some proportion of them.

And that is where we come in. Those are

the ones who might enter this synagogue, and even stick around, if:

1. If they are greeted and welcomed

properly.

2. If they make connections with others

in this building.

3. If they get a personal boost, a shot

of meaning, out of the time spent at Temple Israel of Great Neck.

That third item, conveying the meaning of our

brand of Jewish life, is the most difficult of all, because we set the bar higher

in terms of understanding. We dig deeper, and that is hard to convey in

140 characters or less, or even in the context of a Shabbat morning service

that is already chock-full.

But that’s where we should aim. Let’s

talk about why women and men can be understood as equal under Jewish law.

Let’s talk about how modern perspectives on the Torah add to our

understanding. Let’s teach that it’s not all or nothing, glatt or treif.

Let’s engage with those questions that bring meaning to who we are as

modern people, as modern Jews.

Thoughtful analysis of Jewish ideas couched

in a friendly, easily-accessible format that includes a healthy dose of

spiritual openness is one thing that will bring those in that other category

in. That’s where we need to focus our energies.

In the wake of the UJA study, plenty of commentators

lamented the disappearing center of the New York Jewish community. I say,

bring it on. The center is still here, but we have to work harder to pull

others in with us. All we have to do is make it meaningful, and that

invisible line of the Potentially Engaged will start to creep back down.

Shabbat shalom.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson