The Hebrew root ק-ד-ש, which is spun out into many forms throughout Jewish text and liturgy, originally means "separate" or "distinct." Those things which are קדוש / qadosh, "holy," have been set aside for a particular, non-ordinary purpose. The Shabbat, for example, is a day that is set apart from the other six ordinary days of the week. At a Jewish wedding, the bride and groom are joined to each other when the groom says, הרי את מקודשת לי / harei at mequddeshet li, "Behold, you are sanctified to me...", and thus they are set apart from everybody else and committed to each other. And so forth.

|

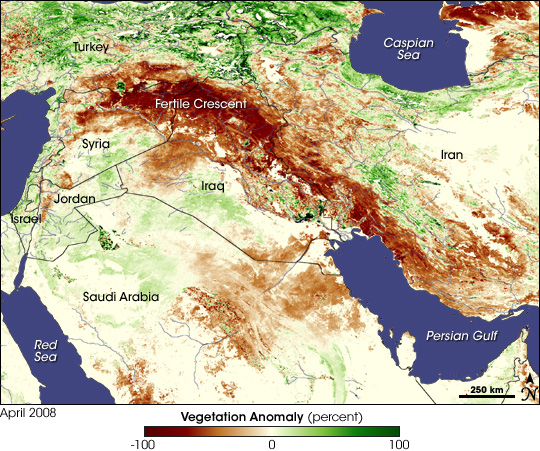

| From NASA, a satellite photo showing drought in the Fertile Crescent in 2008. |

In Parashat Lekh Lekha, Abram is instructed by God to leave his home in what is today Iraq and venture all the way to the other end of the Fertile Crescent to what is today Israel. The Torah tells us neither why Abram was chosen, nor why the destination is Israel; Abram himself does not even seem to know where he is going or why.

But there is no question that Abram's journey is a spiritual one, a quest for holiness that takes him out of his ordinary environment to someplace new, a place where he will be set apart. As the father of monotheism and of two sons from whom Muslims, Christians and Jews see themselves as being descended (at least theologically, if not genetically), Abram is himself becoming holy and creating a new way for all who follow to seek holiness. He is a pioneer of sanctification, one who exemplifies the pursuit of distinctiveness that marks the Abrahamic faiths by taking the extreme path of physical relocation to balance his internal journey.

Fortunately, we do not have to pick up and move to seek holiness. In Judaism, sometimes the act of differentiation that makes us holy is as simple as picking up a book. Now go and learn it.

Shabbat shalom!

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson