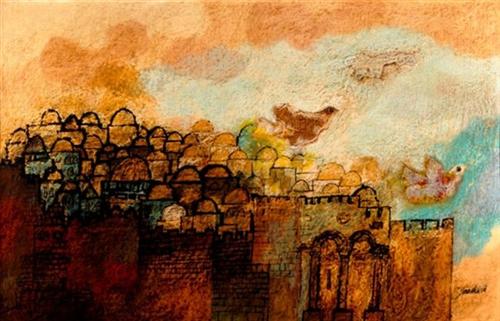

I am a big fan of Israeli pop music, particularly the way it tells the story of Israel. Not necessarily the explicit story, the history-book story, but the implicit story of who Israelis are, where they came from, what they value, and what life is like in Israel. Back in the ‘80s, when I spent a few summers at Camp Ramah in New England, and participated in USY, Israeli pop tunes saturated my life, particularly the Eurovision festival entries (Halleluyah, Abanibi, Hai, etc.) and the “Hasidic” song festivals (Adon Olam, etc.). As an American Jewish teenager who loved Israel, these songs created something of a background soundtrack to my life. And there was no song more resonant than Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, the song by Naomi Shemer that told the story of loss and reunification of the holiest place in Israel, the city that occupies such a special place in the hearts of so many of us. To this day, it seems that this song is the best-known and best-loved of the entire Israeli pop canon, at least in this hemisphere.

On Wednesday morning I heard about the Palestinian man with links to Hamas who plowed his car into a group of innocent Israelis waiting for a train at the Shim’on HaTzaddiq station on the new light rail line, killing one and injuring a dozen more people. This follows a similar attack two weeks ago in which a three-month-old baby girl and an Ecuadorean tourist were killed, and another incident in which an American-born rabbi, Yehuda Glick, was shot and critically wounded for advocating to allow Jews to pray on the Temple Mount.

And I realized that I had no choice but to pause to grieve for Jerusalem, the city whose name may be derived from ‘Ir Shalom, the City of Peace.

Where is the Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, the Jerusalem of Gold that we all know and love? Does that song merely capture a fleeting dream, a candle of hope and unity that only flickered briefly before being snuffed out by the intractable reality on the ground? Is the zahav, the gold, merely that of a rising flame of tension, disunity, and instigation?

I lived in Jerusalem in the year 2000 for about seven months, for my first semester in Cantorial School at the Schechter Institute for Jewish Studies, just before the Second Intifada broke out. It was a relativly peaceful and even optimistic time in Israel. Just a few years after the Oslo Accords, peace was coming. Areas of the West Bank and Gaza had been turned over to the Palestinians. There was new development and cooperation on matters of security and trade. No part of Jerusalem seemed unsafe, and I walked the streets of East Jerusalem and the Arab quarters of the Old City without fear.

But oh, how things have changed. It was, you may recall, the failure of the Camp David summit in July of 2000 that ultimately led to the Intifada. I had just returned to New York to continue my studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary when the City of Peace became the city of bus and cafe bombings.

Things cooled down again after a few years. Israel built the separation fence (which in places is a wall), which worked quite well in keeping would-be attackers out of the Jewish population centers. Jerusalem’s brand new light rail line, which took years to build, opened in 2011, and the optics of a, thoroughly modern commuter train running alongside the Old City walls built by the Ottoman Turks in the 16th century are truly inspiring. I have been on the train a few times, and am always captivated by its tri-lingual scrolling sign, announcing the next station in Hebrew, Arabic and English. The cool thing is that, since English goes from left to right and the other languages from right to left, the info scrolls in both directions.

But it is this light rail system, originally built to serve both Arab and Jewish neighborhoods of Jerusalem (the population of which is 37% Arab), that has unfortunately been a focal point of some of the recent violence. It was the target of attacks in July by Palestinian youths, who sacked the stations in their areas. So the municipality stopped running the trains there. The two deadly car attacks of the last couple of weeks took place at rail stations, easy targets for terrorists. This symbol of old and new, of coexistence and cooperation and shared economy and destinations, of progress and promise, has devolved into a symbol of hatred and resentment, of failure and intransigence, of murder and riots.

To quell the angry mobs of Palestinian protesters last week, Israel ordered a full shutdown of the Temple Mount for a day, the first time since the summer of 2000, igniting even more tension within the city as well as angering Israel’s mostly-cordial Arab neighbors in Jordan, who are still somewhat in control of what goes on on top of the Temple Mount plaza. Jerusalem is at a rolling boil of hatred, anger, fear, and grief.

Among the many, many things I learned about in rabbinical school are the basic principles of “family therapy.” Family therapists see each family as a system of interconnected personalities, and that when a family system is not functioning in equilibrium, then one or more of the people in the system misbehave and cause emotional damage. Often, the way to fix such a family system is to make a significant change in the structure. The hard part is knowing what must be changed.

The parashah that we read today describes the residents of Jerusalem as being from the same family - Abraham’s sons Ishmael and Isaac are the patriarchs of the Jews and the Arabs, respectively, and the Torah presents both of them as having a certain role to play in the world, siring two great nations. Let’s face it - Muslim, Christian and Jew, Israeli and Arab, we are one big family system that is misfiring all over the place.

As if to draw a fine point on this picture, Israel’s new President, Reuven Rivlin, a right-wing politician who supports settlements and rejects the two-state solution, said in a speech two weeks ago (as quoted in an article in the current Jewish Week): “The tension between Jews and Arabs within the State of Israel has risen to record heights, and the relationship between all parties has reached a new low. We have all witnessed the shocking sequence of incidents and violence taking place by both sides… It is time to honestly admit that Israeli society is sick - and it is our duty to treat this disease.”

With every terrorist attack, we, the Jews, the Israeli public are driven further away from seeking a negotiated resolution to the current situation. And that is an understandable response. As has often been noted, whenever Israel has retreated, terrorist groups have been emboldened.

But this observation is always made from the position of defeatism. The message is, “Nothing should change, because change has never been good for us.” I cannot accept that message.

Returning to President Rivlin, I offer his words given at an amazing speech in Kafr Qasm, an Israeli Arab town, where he spoke at the annual commemoration of the 1956 massacre of 48 Arab residents of the town by Israeli troops. He acknowledged the discrimination that Israeli Arabs have faced at the hands of the Jewish majority, and exhorted Arabs and Jews to take a step forward together based on “mutual respect and commitment”:

“As a Jew, I expect from my coreligionists, to take responsibility for our lives here, so as President of Israel, as your President, I also expect you to take that same responsibility. The Arab population in Israel, and the Arab leaders in Israel, must take a clear stand against violence and terrorism.”

The current escalation threatens the very foundations of the City of Peace, and it will not go away until there are fundamental changes in the family system. Those changes will have to be that, for the sake of Jerusalem, the Palestinians renounce terrorism, that PA President Mahmoud Abbas stops making inflammatory statements that seem to sympathize with terrorists, that Israel ceases demolishing homes, even the illegal ones, in the Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem, and at least temporarily stops issuing building tenders for new construction for Jewish homes in disputed areas, and that both sides return to the table. As a family, we have to talk to each other.

We have no other choice. The only other option is the status quo, and we see how well that is working. The family system is broken.

We read this morning one of the most well-known and controversial stories in the Torah, the Aqedat Yitzhaq, the Binding of Isaac. Tradition tells us that it takes place on Mt. Moriah, which we today know as the Temple Mount. It is the Torah’s way of telling us that Jerusalem is the holiest place in the world, the location where a paradigm shift in our relationship with God took place. And, of course, Christians and Muslims believe this city to be holy as well.

Prayer, ladies and gentlemen, is not just a request for things that we want, it is also a blueprint for a world that could be. We should pray for those killed and injured in this conflict. But we also have to pray for the holy city of Jerusalem, and hold out hope that this situation will change.

שַׁאֲלוּ שְׁלוֹם יְרוּשָׁלִָם; יִשְׁלָיוּ, אֹהֲבָיִךְ. יְהִי-שָׁלוֹם בְּחֵילֵךְ, שַׁלְוָה, בְּאַרְמְנוֹתָיִךְ.Pray for the peace of Jerusalem: “May those who love you be at peace. May there be well-being within your ramparts, peace in your citadels.”

(Psalm 122:6-7)

Giving up hope is not an option. We must continue to sing Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, but also to invoke Psalm 122, to pray for the peace of Jerusalem, and to continue to place that before us as a goal. We must hope that change will come; if we give up that hope, then there will never be peace in the City of Peace.

Shabbat shalom.