Every year around this time, Rabbi Stecker and I find

ourselves working very hard to help others with their sedarim. Starting

a month before Pesah, we teach seder skills and material

in a wide variety of formats and before many different audiences: the Men’s

Club, the Nitzanim Family Connection, the Religious School Bet class, the

Shabbat afternoon se’udah shelisheet crowd, and so forth.

Pesah is, as I am sure many of you know, the most-practiced ritual

of the Jewish year among American Jews. About 4 out of 5 of us show up to a seder

of some sort, and for some of those Jews, this will be the ONLY Jewish

experience that they will have in 5773; far more people come to a seder than

seek forgiveness in the traditional ways on Yom Kippur. For those of us

who are regulars, who are committed to Jewish life, this is an opportunity to

engage, and I encourage everybody here to reach out as ambassadors of Jewish

living.

Related to that, I think that now is the time to start

asking the hard questions about American Judaism, and talk about them around

the seder table. After all, the seder is meant to be not only a

meal, but also a discussion. It is modeled after the Greek symposium, an ancient

type of dinner party that featured food, wine, discussion, and entertainment,

all of which was enjoyed while reclining. We have the haggadah to guide

us through our Jewish symposium. But the haggadah is only a guideline, a

kind of framework: you can fulfill your Pesah obligation of “Vehigadta

levinkha bayom hahu,” (Shemot / Exodus 13:8) of telling the story to

your children on that day by reading it from the haggadah, but you can also

fulfill it if you leave the printed page. The very word, “haggadah,” is derived from the same

shoresh / Hebrew root of the commandment “vehigadta” in that

verse; haggadah means telling, and does not necessarily mean reciting

from a book.

Telling the story of Pesah, of traveling

from slavery to freedom, usually raises a few questions. Well, four at least.

But in fulfilling the obligation of “vehigadta levinkha,” of telling

your children, should we not connect our modern world with our ancient tales?

Here are four more questions for discussion, questions that we should all be

asking around the table on Monday and Tuesday night:

1. On this Festival of Freedom, how will we ensure that

our own contemporary freedom does not lessen, or indeed sever our connection

with Judaism?

2. Is it indeed possible for us to continue to be Jewish

while enjoying full assimilation into American society? Or is the only recourse

to preserve our Jewish identity, as the Haredi world seems to believe, to

self-segregate, i.e. to “enslave” ourselves, to curtail our independence?

3. What kind of Jewish world do we want in the future?

4. What are the things that we can do to make sure that

our grandchildren have strong Jewish identities, and healthy, modern and open synagogue

communities where they can practice comfortably?

And, like the traditional Four Questions of the seder,

these can be summed up in one question: “Where are you headed, Jewishly

speaking?” The question is to be asked, as it is to the Four Sons, in a manner

that is both national and personal.

Let me tell you why these are the essential questions

of our time.

Five years ago, Dr. Arnold Eisen, then the newly-minted

Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, spoke here at Temple Israel.

Responding to the state of the Conservative movement, he said that the decline in

our numbers was not insurmountable, but that if things did not turn around in

5-10 years, the then-future prospects were not so good. Well, it’s been five

years, and (Temple Israel’s relative stability notwithstanding) I have not detected

any real change in the slope of that decline.

Numbers in the Reform movement and in Modern Orthodoxy

are not much better. The only segment within Judaism that is growing rapidly

is, of course, the Haredim, the fervently Orthodox.

There is no question that we Jews have greater freedom

here and now than we have ever had; we are fully integrated into American

society. There are few remaining barriers to Jews: We are not excluded from the

best universities, as some of us were in the first half of the 20th century; we

are welcome at the most prestigious workplaces and social forums in the nation;

we occupy a third of the United States Supreme Court; the idea of a Jewish president

is not beyond the realm of possibility; and much of non-Jewish America is

willing not only to date us but to marry us as well.

There are no surprises here; we have come a long way in a

few generations. Many of you know that statistics (from, for example, the National Jewish Population Survey) have shown the intermarriage rate hovering at about 50%

for more than two decades. Related numbers show that children in intermarried

families, on the whole, grow up with a far lower connection to Judaism. There

are, of course, Jews who have married non-Jews who succeed in raising

strongly-identified Jewish children, and there are many non-Jewish parents who

are committed to raising Jewish children -- bringing their kids to synagogue,

Hebrew school, and so forth -- but they are the exception, not the rule.

But really, the issue is not intermarriage, which is I

think merely a symptom of the greater problem. It’s about American Judaism in general,

and particularly non-Orthodox Judaism. It’s time to think critically, not just

about numbers, but the strength of our community’s connection to Judaism.

We know that Orthodoxy, and in particular Haredi

Orthodoxy, is booming. They are growing rapidly, with many children per family,

strong communal interconnection, and of course a zeal for Judaism and Jewish

life. You may have read NY Times columnist David Brooks’ piece on this

recently, a fawning account of his visit to black-hat Brooklyn titled “The Orthodox Surge.”

Brooks reports an excursion to Pomegranate, the top-shelf

kosher grocery store that he likens to the specialty-food supermarket giant Whole

Foods. I will not dwell on the strengths of Brooks’ argument, or its weaknesses.

But in response, Jordana Horn of the Forward wrote an opinion piece that should be mandatory reading at your seder table.

Ms. Horn describes herself as a committed Conservative Jew, and resents Mr.

Brooks’ implication that Orthodoxy holds the Jewish future.

After pointing out that it is possible to be dedicated to

Judaism and not Orthodox, she makes the following observations:

I fear that when my children grow up, they will encounter

a world in which they will have to choose to be Orthodox or secular, and that

no other options will exist — that while Conservative and Reform Jews were busy

building gorgeous edifices of synagogues, they will have neglected to build

communities that ensure their survival.

I long for someone to stand up in Conservative and Reform

synagogues and say, “Hey — if we want our egalitarian models of Judaism to have

a fighting chance in the future, we need to think out of the box.

“We need to put our money where our mouths are

when it comes to ensuring a Jewish future. We need to make sure our young

congregants are on JDate. We need to make sure to reach out to and include

Jewish singles and young families as much as we do senior citizens.

“We need to have a financial plan for making

Jewish nursery school the best possible option, and an accessible one, for

Jewish parents. We need Jewish day care in our synagogues for working parents

so that the synagogue is seen as an indispensable part of life. We need

to have infant and child care in every single service and program we offer.”

Ms. Horn is right on. And she could have said far more.

Not just Chabad, but many variants of Orthodoxy have a tremendously impressive

suite of outreach offerings that are easy to enter; they bring them right to

you. They go where the Jews are, and they invite people in. Ladies and

gentlemen, we say on two nights of every year, in front of all of our friends

and family, “Kol dikhfin yeitei veyeikhul,” “Let all who are hungry,

come and eat.” But aren’t we just paying Aramaic lip service? Are we really working

hard to bring people into our fold?

And furthermore, are we working hard with the people who

are already there at the seder table, young and old, intermarried and

in-married, to give them the tools that they need to live authentically Jewish

lives as mainstream Americans?

Many of you have heard me say this many times in this

space that we in the Conservative movement are committed to Rabbi Mordecai

Waxman’s slogan of “tradition and change.” You know that I am committed to the

Judaism of the Torah and the Talmud, the faith which inspired our ancestors and

sustained them through centuries of misery, poverty, persecution, and wandering

across continents and oceans. You know that I hold steadfast to the principles

that Moses Mendelssohn, as the first emancipated Jew, held dear in the middle

of the 18th century when he successfully joined German society as a practicing Jew. You know that I reject the isolation that the

Haredi world pursues, that I am committed to living as much as an American as a

Jew, that I support the moderate approach to halakhah and interpreting

our canonical texts through a lens that is at once traditional and modern and scholarly.

You know that I, that we at Temple Israel, stand for open engagement with both

the Torah and with science, with egalitarianism and modernity, with Israel and

with America.

And yet I, like Jordana Horn, wonder if my daughter and

her children and grandchildren will have to choose between the Jewish approach

that is stuck in 18th-century Poland and the one that hangs bagel ornaments on

Christmas trees.

So those are the four questions we should be asking our

friends, our family, our children and grandchildren. Where are you going,

Jewishly?

And hey, maybe that’s OK with most of those 80% of

American Jews who show up for a seder. Maybe they do not care if there

is a middle ground to Judaism. But I’d like to think that they do, and that if

we all reach out to them, just like Chabad is doing so successfully, maybe they

would be happy to come around here once in awhile, and not just on a major

holiday or a family simhah.

For extra credit, the followup question is this: If you

do indeed want a middle path to Jewish life, what are you going to do to make

sure it does not disappear? Are you going to marry a Jewish person, or insist

on conversion for a non-Jewish partner, or at the very least, work to agree

that said partner will commit to raising your children as Jews? Are you going

to join a synagogue? Are you going to take your family on vacation to Israel,

rather than Mexico? Are you going to make sure your children obtain a Jewish education?

Are you going to challenge yourself to try on for size just one new mitzvah,

one that is easy and meaningful to you, like lighting Shabbat candles or

blessing your children on Friday night, or studying some Torah? Are you going

to discuss with your children how important it is to you that your grandchildren

know that they are Jewish and why?

After all, what is the use of freedom, and freedom to

practice our religion, if there is only one variety to choose from, and that

variety rejects the very freedom we enjoy, and the secular structures that make

it possible?

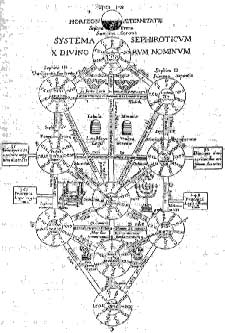

From the second day of Pesah until Shavuot

we count off seven weeks of Sefirat HaOmer, the counting of the

sheaves of grain that our ancestors were commanded by the Torah to do. Although

today we bring no sheaves, we are understand this period as one of self-discipline,

of kabbalistic meditation on the emanations of God, and as a period of preparation

for receiving the Torah on Mt. Sinai. It is a time of study, and as it seems likely

that the theme for our Tikkun Leyl Shavuot will be an examination of the

role and power of the qehillah qedoshah, the synagogue community, I urge

you to begin to consider these themes as we launch into Pesah and

beyond.

Where are you going, Jewishly? Ask these questions around your seder table. Shabbat

shalom and hag sameah.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Temple Israel of Great Neck, Shabbat morning, 3/23/2013.)