I have to make a confession. I am guilty of something. I failed to empathize.

Actually, it was not merely a failure to empathize, but rather a failure to pay attention at all to the news out of Ferguson, Missouri regarding the events of the past summer.In my defense, I was busy paying attention to Israel - the rockets, the bomb shelters, the tunnels, the scenes of destruction and death, the body counts, the anti-Semitic demonstrations, and so forth. I was wringing my hands all summer long, glued to my computer screen, waiting for the next piece of bad news.

So somehow I missed the story that resurfaced, somewhat unpleasantly, this week - the story of Michael Brown, the young man who stole a $46 item from a convenience store, and was subsequently shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson in that suburb of St. Louis. I was only dimly aware that the community of Ferguson erupted in mid-August, and that it attracted attention all over the world. All of that was crowded out because my head and heart were in the Middle East.

I have not spent the subsequent three months following the story - the protests, which endured for weeks afterwards, the investigations, the grand jury. I was busy with the EmptiNesters retreat, the holidays, the Shabbat Project, the Rabbinic Management Institute that I attended in LA two weeks ago, and so forth.

Besides, I’m a rabbi. My position demands of me to pay attention to issues affecting the Jewish community, right? Why should this story be so important? Most of the world has no concept of the complexity of the situation in Israel, and it is my responsibility to be aware of and speak to that. I only have so much time and brainpower.

OK, so I have a long list of excuses, none of which are very good.

I should have paid more attention to this story because it speaks to the very heart of who we are as a people, and what our tradition teaches us about caring for the disenfranchised in our midst. A better reason, however, has really nothing to do with the particulars of this case, but it has everything to do with our role in American society.

I think we - not just we the Jews, but all Americans - are running an empathy deficit. I think we are so wrapped up in ourselves that we are failing to pay attention to those around us who are in need. This is not just about civil rights or race or ethnicity or religion or gender issues or the fragmentation of the American family, but it does include all of those things. There are so many things that divide us today that it is easy to just give up - to throw in the towel, as it were, and just look out for number one, or become desensitized.

What has happened to our public sphere? Why are our politics so broken? One possible reason is that we have all stopped caring about each other. What happens in suburban Missouri stays in Missouri. I’m just going on about my life here in Minneapolis, or Miami, or Michigan, or Manhasset. And yes, we in the Jewish community are just as guilty as all the rest of us.

Maimonides tells us (MT Hilkhot Matanot Aniyim 7:13) that in matters of tzedaqah / charity, we are first obligated to our family, then to the needy of our own town, then to those in another town. While many of us may find ourselves moved and challenged by the events in Israel, our family, we should also be concerned with affairs in our own backyard.

Many of us have known anti-Semitism personally and globally. Certainly the events of this past summer have awakened within the Jewish community concerns that not too long ago seemed somewhat passé. But most of us are not personally experiencing discrimination on a daily basis. But are we aware of the discrimination that others face?

Please consider this thought experiment for a moment:

- You’re leaving work. You’re wearing a suit. You try to get a cab. Not a single one stops for you, even those that are carrying no passengers.

- You’re trying to find an apartment to rent. You call landlord after landlord, only to find that every single one has curiously just been rented, even the less desirable ones.

- You’re a professor at one of the most prestigious universities in the world. You have returned at night from an overseas trip, and your front door jams. As you struggle to open your own front door, a neighbor calls the police, who come to arrest you.

Imagining ourselves in these situations is not so easy; these kinds of things do not happen to most of us. But they do happen on a regular basis to black Americans, who all suffer from various forms of discrimination and humiliation throughout their lives. With respect to their interaction with the police, this reality has resulted in relatively frequent incidents where an officer shoots a young, unarmed black man in a situation that has gone awry.

Consider Amadou Diallou, the 23-year-old Guinean immigrant with no criminal record, shot outside his apartment in the Bronx in 1999 because he was mistaken for a serial rapist.

Consider Sean Bell, the 23-year-old resident of Queens who was leaving his own bachelor party in 2006 when he and his two friends, all unarmed, were shot by police because they thought they overheard one of the men say, “Yo, get my gun.” Bell died.

Consider John Crawford, a 22-year-old man shopping in a Wal-Mart in Ohio who was shot and killed by police, just a few days before the Ferguson incident, because he was carrying an air rifle that he had picked up from a shelf in the store and was carrying it around while shopping.

In all three of those cases, no police officers were convicted of any crimes. Now these are merely anecdotes, and I am not in a position to evaluate these cases in any responsible, legally-correct way. But there are plenty of other examples, and the pattern is undeniable. We have to feel for the families who lost these young men. We should not excuse, but perhaps we can understand the violent reaction that black Americans had to the news surrounding the Ferguson case. We have to grieve for our society as a whole. And we have an obligation to change that reality.

In a report presented to the UN Human Rights Committee by the Sentencing Project, an advocacy organization, statistics show that it is true that young African-American men are more likely to commit certain types of crime. However, it is also true that they are much more likely to be convicted of crimes than whites or Hispanics who commit the same crimes. The report adds the following:

“... [H]igher crime rates cannot fully account for the racial disparity in arrest rates. A growing body of scholarship suggests that a significant portion of such disparity may be attributed to implicit racial bias, the unconscious associations humans make about racial groups...

“Extensive research has shown that in such situations the vast majority of Americans of all races implicitly associate black Americans with adjectives such as “dangerous,” “aggressive,” “violent,” and “criminal.” Since the nature of law enforcement frequently requires police officers to make snap judgments about the danger posed by suspects and the criminal nature of their activity, subconscious racial associations influence the way officers perform their jobs.”

Ladies and gentlemen, we are all saddled with bias. We all make spot judgments about others, consciously or unconsciously, based on their appearance. Any human being who denies this is lying. But one of our tasks as Jews as reinforced over and over throughout the Torah, is to remember what it’s like to be an outsider, as when we were slaves in Egypt, and to treat others accordingly. It is our responsibility to empathize with the plight of the sojourner, the widow, the orphan, the poor, because we understand that as a nation. We may not be able to eliminate our own internal prejudices, but we can certainly challenge ourselves to feel for others and act appropriately.

And this is only heightened by our contemporary reality. Despite the rise of anti-Semitism in the world, we are still living pretty well in America. Except for the rare sideways remark, we are accepted as white (something that was not always true); all doors seem open to us. But that does not give us license to ignore those in our midst for whom many of those doors are still closed. It is all too easy to forget that justice is not necessarily evenly meted out in our society.

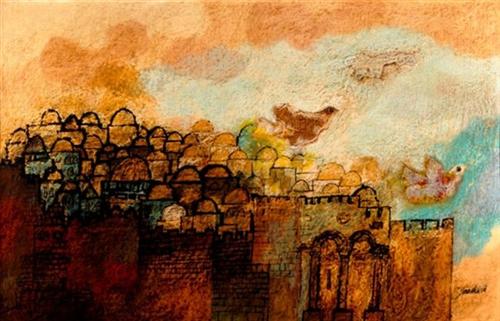

To that end, I would like for our reaction to the case of Michael Brown to be something like the moment that occurs at the end of Jacob’s dream at the beginning of Parashat Vayyetze, which we read this morning. Our hero wakes suddenly after dreaming about angels going up and down the ladder to heaven, and is struck with the realization that, אָכֵן יֵשׁ ה’ בַּמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה; וְאָנֹכִי, לֹא יָדָעְתִּי. “Surely the LORD is present in this place, and I did not know it.” (Gen. 28:16)

Jacob’s new awareness leads him to commit to a new relationship with God. In the same way, the Ferguson events might elevate our connection with God by raising our own awareness of what some of our fellow citizens endure every day. That awareness should spur us to action.

My point here is not to excuse either Michael Brown, an alleged petty thief who may have resisted arrest, or Officer Darren Wilson, who may have overreacted to the situation. This is not about race. Rather, my goal on this Shabbat Thanksgiving, a time that we as a nation remember to be grateful for what we have, is to remind us that our gratitude can only be amplified when we remember to feel for the other. It is a primary goal of the Torah to help us to see beyond ourselves, to consider how our actions affect others, and to be aware of our interconnectedness to all our fellow citizens as a part of this society, in short, to be empathic. Even though we all arrived here on different boats, some of us enthusiastically and some of us in literal chains, we are all in the same boat when it comes to building a just society.

Our tradition believes that all people, not just the Jews, are obligated to the Sheva Mitzvot Benei Noah, the seven mitzvot given to Noah following the Flood. One of those mitzvot is the commandment to foster justice. Maimonides suggests that if you do not live in a place with an honest justice system, then you should move away. I do not think that anybody could credibly make that charge about these United States. However, it is surely worth noting that our society is still a work in progress, and that cultivating empathy for all people, and not just our people, will go a long way toward building that nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Temple Israel of Great Neck, Shabbat morning, 11/29/2014.)