Ms. Manji had recently published her first book, The Trouble With Islam Today, in which she identifies many of the things that we in the West see as problematic

within the Muslim world: its treatment of women, honor killings*, female

genital cutting, slavery, and, of course, international terrorism and

anti-Semitism. There is no question that much of today’s anti-Jewish and

anti-Israeli hatred is coming from Muslims. (Last I heard, the suspects in the

tragic bombing in Boston were Chechen; it is likely that they are Muslims.)

Knowing that she was standing before a group of Conservative Jews, rabbis

and cantors and future clergy, Ms. Manji expressed hope that, while the Islam

of the East is saddled with a range of social ills, the future of moderate Islam,

something similar to non-Orthodox Judaism, lies in the West. She also pointed

to a concept in historical Islamic jurisprudence called “ijtihad,” which

fell out of common practice around the 10th century CE. Ijtihad is

effectively the elevation of the self, the ability to think critically and make

one’s own decisions within the sphere of shari’a, Islamic law. Ms. Manji

advocates a return of ijtihad to Islam to bring the Muslim world into

modernity, that introspection and self-criticism coming from Muslims in the

West would yield a positive effect on the rest of Islam.

A brief grammar note: Arabic, like its sister language, Hebrew, has binyanim,

verb constructs that modify a shoresh, three or four root letters, into related

verb forms. One of these binyanim in Hebrew is reflexive, and is

referred to as hitpa’el, the “hit” at the beginning being the major

sign of reflexive-ness. When found in this binyan, a verb reflects back on

the speaker.**

I am by no means an expert in Arabic grammar. However, I do know that ijtihad

is a reflexive form of the root from which the well-known word jihad,

meaning “struggle”, is derived. So “ijtihad” literally means,

“struggle with oneself.”

Now, I have just mentioned shari’a and jihad, words which

have probably raised the hackles of more than a few of us in this room. Why is

that? I’ll return to that question in a moment. First, a few words about the Torah.

We read today in Parashat Qedoshim an

extensive list of laws known to scholars as “the Holiness Code.” They include

such diverse topics as honoring one’s parents, leaving some of your produce for

the poor, treating animals respectfully, dealing fairly with your business

customers, and so forth. It is a fascinating look into the world of our

ancestors and their expectations for how to interact with others. (It was also,

as luck would have it, my Bar Mitzvah parashah, and I appreciate it all

the more so today.)

Qedoshim (and the rest of

Jewish tradition) should be studied not just as a law code, not merely a

framework for righteous behavior, but also as a means to improving ourselves.

Why does the Torah need to tell us to leave the corners of our fields unharvested,

so that poor people in our midst can come and take food? Because our

inclination is to be greedy, to take more for ourselves. The Torah is therefore

challenging us to rise above our base natures, to struggle internally over what

we want to do vs. what we should do. And this is a struggle with which we are

all intimately familiar.

I would like to highlight one verse (Lev. 19:16):

לֹא-תֵלֵךְ רָכִיל בְּעַמֶּיךָ, לֹא תַעֲמֹד עַל-דַּם רֵעֶךָ: אֲנִי ה'.Lo telekh rakhil be’amekha; lo ta’amod al dam reiekha, ani Adonai.Do not go as a gossip among your people; do not profit by the blood of your fellow, I am Adonai.

While at first, the two halves of this verse do not seem to relate to each

other, the 12th century Spanish commentator Avraham Ibn Ezra tells us the

following:

Rather, “do not take a stand against the blood of your fellow” - do not conspire with violent men against him. It is obvious that many people have been murdered and otherwise killed on account of talebearing.

Ibn Ezra’s point is that talking ill of others causes bloodshed, because by

contributing to the fear and hatred of others in your midst, you might actually

inspire dangerous people to take action, even if that is not your intent.

I raise this because of the complicated issues surrounding the visit of the

infamous Pamela Geller to our community last Sunday. Geller is an activist who

decries the “Islamization” of America, and along with fellow activist Robert

Spencer, the founder of “Stop Islamization of America,” or SIOA. This organization

has been identified by the Anti-Defamation

League (ADL) as “deeply problematic,” and characterized by the Southern Poverty Law Center as “anti-Muslim,”

an analog to “anti-Semitic.” Geller is probably best known for leading the

charge against the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque.” You might also know her for

these signs, which were placed in the New York subways by her other organization,

the American Freedom Defense Initiative, only after a court battle to win the

right to place them:

In addition to these endeavors, she regularly makes inflammatory and “preposterous”

(according to the SPLC) statements. She promotes the idea of an extremist

Muslim conspiracy in our midst, involving our government, our media, and even

“left-wing rabbis” to impose shari’a on all of us non-Muslims. She

claims that there is no such thing as “moderate” Islam, and is fond of calling

her critics “Nazis” or “leftists” or “Islamic supremacists.”

She spoke last Sunday here in Great Neck at the local Chabad synagogue.

There were perhaps as many as 500 people in attendance.

Ladies and gentlemen, I feel that Ms. Geller should not be given a forum at

any synagogue. She puts herself forward as a defender of Israel, but what she

and her organization are doing is characterized in no uncertain terms by the

director of the ADL’s New York office, Etzion Neuer, as “bigotry.”

There is no question that the Islamic world has much to answer for. Many of

the statements and actions by individual Muslims around the world that Ms.

Geller points to on her website and at speaking engagements are, unfortunately,

true. And those in their midst that tolerate hatred and despicable acts are

guilty accomplices, and should rightly be taken to task.

However, that does not give us a green light to engage in the same types of

hatred. And that does not mean that there is credible conspiracy to turn us all

into Muslims.

Ms. Geller and her partners, Mr. Spencer and David Yerushalmi, the guy who is working hard to get state

legislatures to pass ordinances that will prevent judges from consulting

shari’ah law, and who also introduced her at Chabad on Sunday,

promote themselves as fighting jihad. But what they are actually doing is

something truly nefarious: they are creating a fear of something that does not

really exist. There are no American courts that are giving American Muslims a

pass on honor killings; the few American cases that I could find through

Internet searches have resulted in jail time for the guilty parties. There is no

attempt by anybody to bring Islamic law to public schools, or to force anybody

to wear a veil, or to invade our public space in a way that violates our rights

to live and practice our religion freely as Americans.

To imply that these things are in fact happening, when they are not, is talebearing.

This is gossip. This is painting all Muslims with one brush.

Furthermore, these figures are exploiting the Jewish community’s fears

regarding Israel. Israel has a much higher Muslim population, percentage-wise,

than the United States, has Muslim judges (I have, in fact, been in an Israeli

courtroom presided over by such a judge), and has a division within the Ministry of the Interior devoted to

providing religious services to Israeli Muslims, and there is no fear in the Jewish state of creeping shari’a law.

Geller and her friends are really doing something shameful: they are

deceiving ordinary American Jews into fearing something that just is not there.

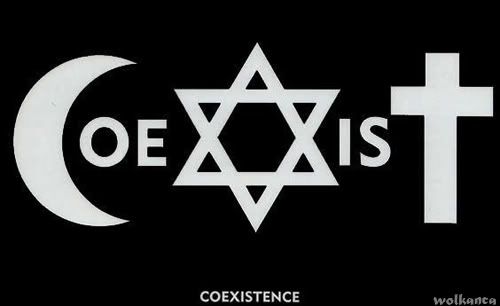

And they are further sowing division, not just between Jews, Christians, and

Muslims, but also causing a wedge between Jews right here in Great Neck and

elsewhere.

This is standing by the metaphorical blood of your neighbor. And we Jews,

with the lessons that we have learned from centuries of oppression, of blood

libels and pogroms and genocide, we know that fear and hatred leads to the

shedding of actual blood.

In 1790, following his visit to the Sephardic synagogue in Newport, Rhode

Island, he President George Washington wrote the following in a letter

to the congregation:

The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves

for giving to Mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy

of imitation... For happily the Government of the United States, which gives

to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that

they who live under its protection, should demean themselves as good citizens.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is our duty as American Jews to continue to

maintain the ideals that President Washington invoked. To be pro-Israel, one

need not be anti-Muslim. And bigotry and persecution have no place in our

synagogues, in our holy places. We cannot lower ourselves to the level of the

anti-Semites, because that just gives them more credibility, and more ammunition

for their hateful ways.

Rather, it is our duty to reach out to and support the moderate Muslims in

this world, and there are many, particularly here in North America. As Irshad

Manji has suggested, by elevating the moderates, the ones who are willing to

engage in introspection through the ancient Muslim tenet of ijtihad, we

have the potential to change this equation for the better. Change will not come

unless we raise the bar of dialogue, rather than lowering it; Pamela Geller’s

hateful recriminations leave no room for respectful disagreement.

As a footnote, I would like to add that if Ms. Geller ever reads this

sermon on my blog, she will surely call me all sorts of names, as that is how

she works. She will suggest that I am part of the vast conspiracy to suppress

what she calls “the truth.” None of these accusations will be true; but her

doing so will prove my point.

The truth, ladies and gentlemen, is that we cannot be naive about the

dangers posed by fundamentalists and zealots of all stripes, Muslim, Jewish,

Christian, Hindu, and so forth. But there are more productive ways for us to

save lives and support Israel than to succumb to fear-mongering in our

community.

It is for sins of talebearing that Ms. Geller and her colleagues should be ignored.

They have a right to say what they want, just as anti-Israel activists do, just

as, I suppose, outright hate groups do, as long as it does not incite violence.

But let us not give them a forum; let us give bigotry no sanction.

Shabbat shalom.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Temple Israel of Great Neck, Shabbat morning, 4/20/2013.)

* The origin of honor killings is cultural, not endorsed by Muslim leaders;

while it is abhorrent, it far predates the birth of Islam, and is related to

the very principles we read in two separate passages in our parashah today,

that mandate death for forbidden sexual liaisons. While Jewish society never

enforced these killings, some traditional societies, including many which

became Muslim in the 6th century and thereafter, maintained them. It is of

course a shame and embarrassment that this practice still exists; perhaps as

many as 5000 people are killed by their own family members each year

world-wide. Muslim Men Against Domestic Abuse is one organization that is working to prevent these killings.

** Some Hebrew examples are:

- lehit’orer, to wake up

- lehitlabbesh, to dress oneself

- lehitpallel, to pray (literally, to judge oneself)

- lehitlonnen, to complain (interesting that this reflects back on oneself - not so good for the Jews, right?)